Overtraining and Ageing: When “More” Backfires on Recovery, Hormones and Longevity

Training is meant to build resilience — but chronic overload without recovery shifts the body into persistent stress, slowing repair and accelerating biological wear.

← Back to: Biology of Ageing Explained

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not provide medical advice. If you experience persistent fatigue, unexplained performance decline, hormonal symptoms or recurrent illness, consult a qualified healthcare professional.

Exercise is one of the most powerful tools for healthy ageing — until it isn’t.

When training stress consistently exceeds recovery capacity, the body shifts from adaptation into chronic stress physiology. Performance stalls, fatigue accumulates, sleep degrades and injury risk rises.

Over time, this pattern can quietly accelerate biological wear rather than building resilience.

This guide explains what overtraining actually is, how it affects ageing biology, how to recognise early warning signs, and how to rebuild a sustainable training baseline.

Personal observation: Some of my worst plateaus came when I confused discipline with recovery denial. Progress restarted only when volume dropped and sleep became non-negotiable.

1) The simple explanation

Training creates stress.

Recovery converts stress into adaptation.

Overtraining happens when recovery never catches up.

Instead of getting stronger, the body stays stuck in a stressed, inflamed, under-repaired state.

This breaks the hormesis loop described in Exercise as Hormesis.

2) What overtraining actually means

Overtraining exists on a spectrum:

- Functional overreaching: short-term fatigue that resolves with rest

- Non-functional overreaching: prolonged fatigue and stalled performance

- Overtraining syndrome: persistent dysfunction lasting months

Most people hover unknowingly in the middle category.

3) Chronic stress physiology and ageing

Persistent training stress elevates cortisol and sympathetic nervous system activity.

This impairs sleep, raises inflammation, destabilises blood sugar and suppresses repair pathways.

Over time, this contributes to inflammaging and accelerated biological ageing.

Related: Stress and Longevity.

4) Hormonal disruption and recovery debt

Chronic overload can disrupt:

- testosterone and oestrogen balance

- thyroid signalling

- growth hormone secretion

- sleep architecture

This reduces tissue repair and metabolic stability.

5) Immune suppression and inflammation

Excessive training suppresses immune function while raising baseline inflammation.

This increases illness susceptibility and slows recovery.

See: Immune Ageing.

6) Mitochondria, fatigue and oxidative load

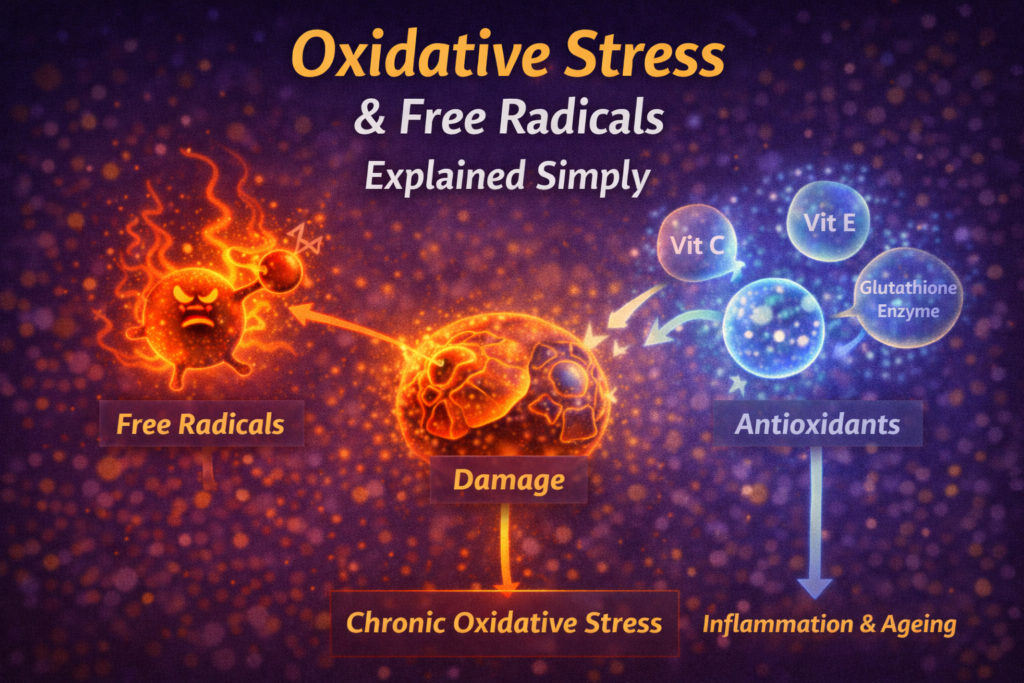

Overtraining increases oxidative stress and mitochondrial strain.

Without sufficient recovery, mitochondrial repair lags — reducing energy availability and increasing fatigue sensitivity.

Related: Oxidative Stress Explained.

7) Early warning signs of overtraining

- persistent fatigue despite rest

- declining performance

- elevated resting heart rate

- falling HRV

- sleep disruption

- low motivation or irritability

- recurrent illness

- nagging injuries

Tracking tools can help if used wisely: Wearables & Recovery Tracking.

8) How to reverse overtraining safely

Reduce volume and intensity

Short-term reduction accelerates recovery.

Prioritise sleep

Sleep drives hormonal and neural repair.

Fuel adequately

Underfueling amplifies stress physiology.

Restore low-intensity movement

Gentle aerobic work supports recovery.

Reduce non-training stress

Psychological stress counts toward total load.

9) How to train sustainably long-term

- periodise intensity

- protect sleep windows

- respect deloads

- track subjective recovery

- avoid identity-based training pressure

Long-term consistency beats short-term heroics.

FAQ

Is overtraining common in recreational athletes?

Yes — especially when life stress is high.

How long does recovery take?

Weeks to months depending on severity.

Should I stop training completely?

Rarely — but intensity often needs reduction.

Does age increase risk?

Recovery capacity declines with age.

Final takeaway

More training is not always better for longevity.

Intelligent recovery protects resilience and slows biological wear.

— Simon

References

- Meeusen R et al. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome. European Journal of Sport Science.

- Smith LL. (2000). Cytokine hypothesis of overtraining. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

Simon is the creator of Longevity Simplified, where he breaks down complex science into simple, practical habits anyone can follow. He focuses on evidence-based approaches to movement, sleep, stress and nutrition to help people improve their healthspan.